Between 19 she recorded at least five versions of the tune with slightly modified lyrics.

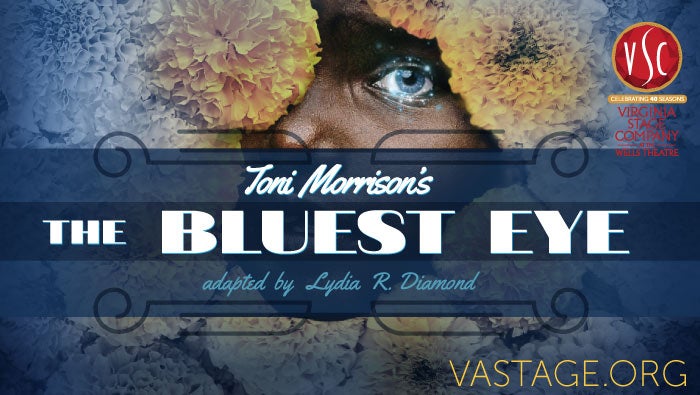

īefore turning to the novel, let us first make a brief detour to the work of another creative genius, Billie Holiday, “Lady Day,” and her song, “Billie’s Blues.” First recorded for Columbia in 1936, the middle of the Great Depression, “Billie’s Blues” was one of Lady Day’s most famous songs and one of the rare formal blues that she sang. Although critics have rightly focused on that novel’s portrayal of the devastating consequences of internalized white supremacy on its protagonist, Pecola, The Bluest Eye also attends to acts of altruism and goodness undertaken for the benefit of the vulnerable child.

And, significantly, this concern with goodness is embedded within her efforts to articulate an ethics that informs the actions of working-class Black communities. Indeed, a return to her first novel, The Bluest Eye, reveals a concern with notions of goodness was apparent from even then. “Writing and trying to find language for goodness is all I have ever done in the novel.” 1 She argues that literary language is most often devoted to evil. Morrison also noted within the past few years that her project includes an effort to try and find a language for goodness. In addition to this important and necessary work, or perhaps because of it, her fiction reveals alternative meanings and worldviews posited in the languages of the marginalized and dispossessed, those most often the subjects of her fiction. Toni Morrison long noted a central mission of her fiction is to identify and dismantle racist language and to remove the dominance and the power of the white gaze.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)